Hakko 936 LED Modification

electronics repair

Overview

I love my Hakko 936 soldering iron. I bought it second hand a couple years ago because I couldn’t afford a better iron. Turns out I didn’t need a better iron. The Hakko 936 is a great soldering iron, and I’ve only ever had one problem with it. The LED…

The way the LED on the Hakko 936 soldering iron presents a lot of information to the user. When the iron is heating up, the LED on. When the iron has reached it’s set temperature it goes off and begins to flash. The only problem is the LED flashes very slowly. After every solder job, because I’m a little scatterbrained, I have to ask myself, “Did I turn off my iron?” Then I have to stare at the LED until the next flash, or until it doesn’t flash. That five seconds of waiting is excruciating, and I finally decided to do something about it.

Turns out, Dave has an episode of eevblog where he does the same thing, with his Hakko FX-888. But because the iron is digitally controlled, it ends up being a lot harder than he thought. Luckily, the LED hack for the Hakko 936 is simple.

The Hack

Probing the circuit with my oscilloscope revealed that when the LED was lit, it was being driven by the 24VAC from the transformer. My suspicion was that the LED duty cycle was the actual duty cycle of the heating element. Looking at the simple one layer board I noticed that the LED was being driven from the uPC1701C chip, which is a zero voltage switch that is used to drive the triac. I googled the part number, and the schematic of the Hakko 936 just to be safe and found that the LED is driven by the comparator’s output. This confirmed my suspicions that the LED’s duty cycle was the same as the heater’s duty cycle. Here’s the link to the Hakko 936 schematic I found online, apparently rendered by Tom Hammond (Thanks, Tom). It’s actually quite beautiful. Amazing what you can do with a jelly bean op-amp. Too often when I think control loop I automatically think software. Also, here’s a link to the datasheet of the zero voltage switch.

There was one problem before I could get started though. I only have one soldering iron. Just like a doctor can’t (or shouldn’t) do surgery on himself, I couldn’t solder on my soldering iron using said soldering iron. At the bottom of my toolbox, I had one of those battery-operated soldering irons from Weller. It’s not a bad product, but soldering on batteries sucks. Even worse than that, I didn’t have any double A’s. So I had to hack this iron before I could hack the other iron.

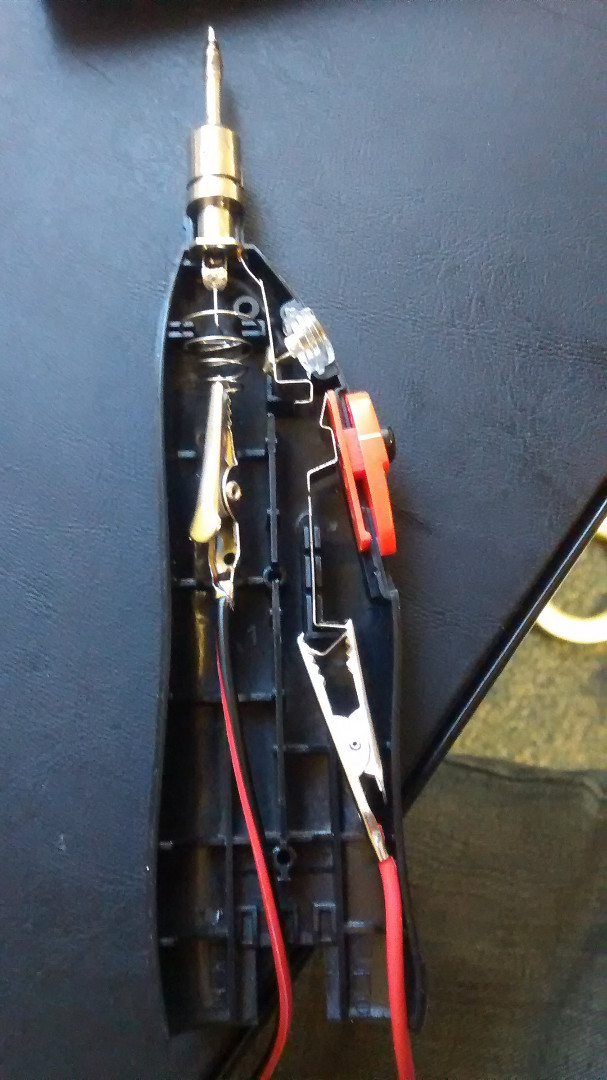

This is the unmodified portable soldering iron.

Portable soldering iron with power supply leads attached.

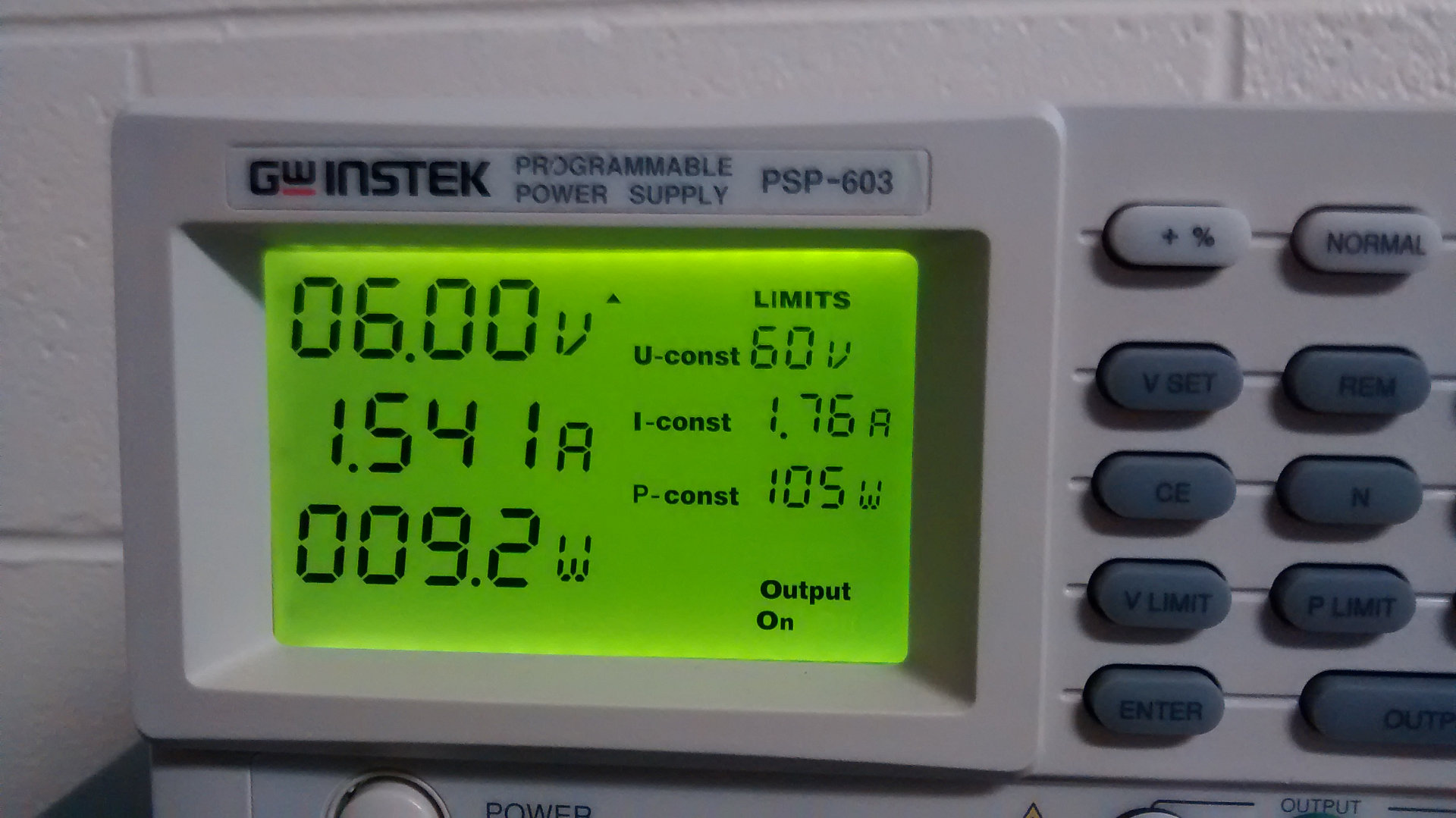

I took it apart, attached the alligator clips from my power supply, and put it back together. First, I tested the iron at 4.5 V, because it originally had 3 double-A batteries, which are a nominal 1.5 V each. It was able to melt solder after warming up, but it couldn’t melt the joint I needed to melt. I was trying to disconnect the socket which the iron plugs into so that I could take the front panel off of the control board. The solder joints for the pins on the socket were too big, and the iron couldn’t melt through the whole joint. I turned up the supply voltage to 6V, and I added a piece of tape over the button that turns the iron on. The tape didn’t hold the button all the way down but made it significantly easier to push. The iron drew a little over 1.5 amps at 6 volts and was able to melt the solder join easily. Also, with the tape making the button much easier to push, I could cycle the power on and off with my hand, sort of like a very slow PWM signal to try to keep the tip from overheating.

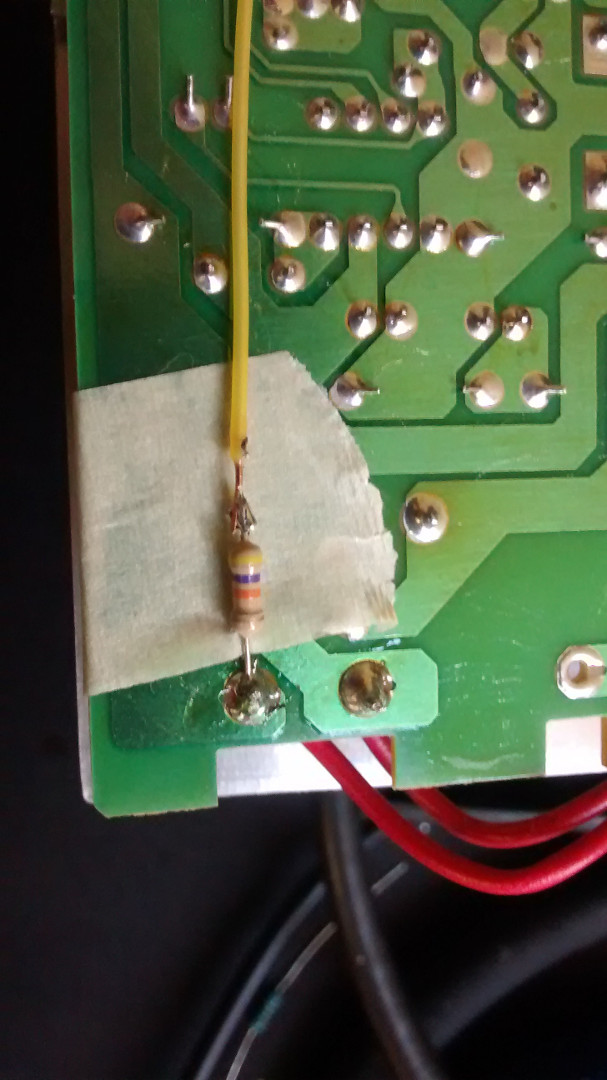

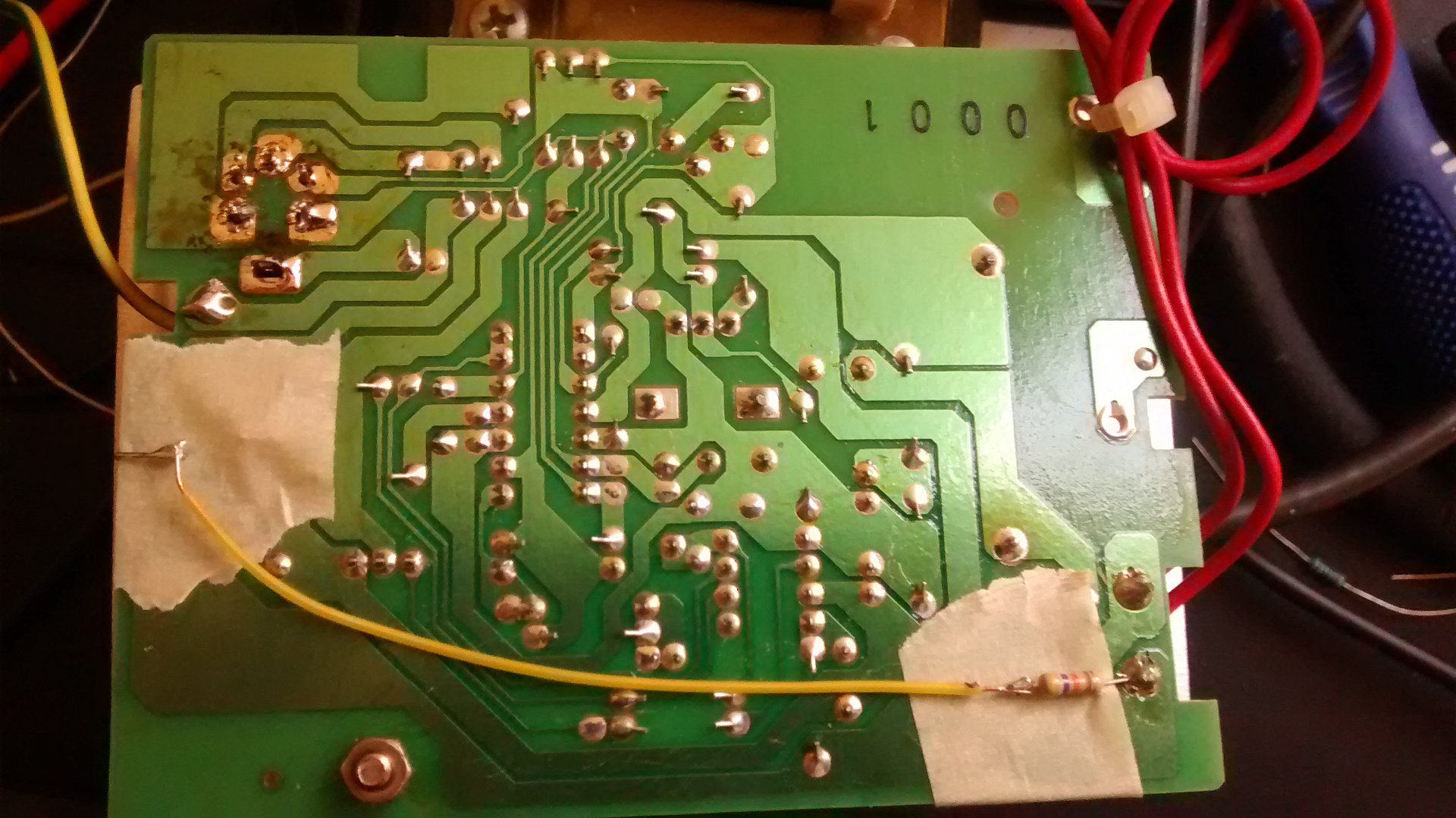

I had a few RGB LED’s in my parts bin, so I decided to use that as the solution. I cut off the blue lead altogether because I didn’t plan on using it. The LED’s I had were common cathode, so I decided to wire the red leg and the cathode exactly where the old LED was. I even reused the standoff. Then I connected the green leg to the 24 VAC power pin through a resistor. I didn’t want it to be too bright, so I used a 47 kOhm resistor. I didn’t want to risk the solder joints poking through the solder mask, so I decided to put down a piece of tape. I couldn’t find my electrical tape and figured since it isn’t even that necessary in the first place, it would be okay to use masking tape. The final bodge didn’t look that bad!

Green Leg from the other side of the PCB.

Bodged resistor attached to transformer tap.

I put on some more tape to hold everything in place and put it back together. It worked like a treat!

The final hack. I re-soldered the connector, but I purposefully did a bad job (as can be seen in the picture) in case I needed to de-solder it again. After I confirmed that It was working I soldered it more permanently.

Check out the video of it in action. It looks a lot brighter in the video than it is in real life. Probably because I’m looking at an LED straight on with a cell phone camera. Because the green LED is always on, the LED is yellow while heating (red + green), and just green when not.