Scraping the Web with Python

programming python

Overview

Yes, I know that tool in the header image is called a plane, not a scraper, but this post is about scraping, scraping web pages. I am not sure if what I am doing in this post is technically web scraping, as I am only interested in extracting one key piece of data from a specific web page, and I think web scraping usually refers to gathering large amounts of data from multiple sources, but it’s similar enough. The key piece of information that I want to scrap from a website is simple, whether an item is in stock or not.

It all started when I decided to cancel my gym membership and commit to working out at home. With the COVID-19 situation, I didn’t like the idea of going to the gym until things were looking better, and so far, things are not looking better. It seems like a lot of people have had the same idea as weights and home gym equipment in general is almost impossible to find in stock right now. Most of the fitness brands that make home gym equipment have a feature on their websites that lets you create an account and sign up for email notifications for when a particular item is in stock again. Usually, you just have to click the “notify me” button on the product page. Unfortunately, one fitness brand, a brand that I would like to buy some equipment from, lacks this feature. So I decided that rather than check the website fifty times a day while waiting for a particular item I want to come back in stock, I would write a little Python script to do this for me and deploy it on my Raspberry Pi to check every hour or so and send my phone a notification if one of the items I want comes in stock.

Setup

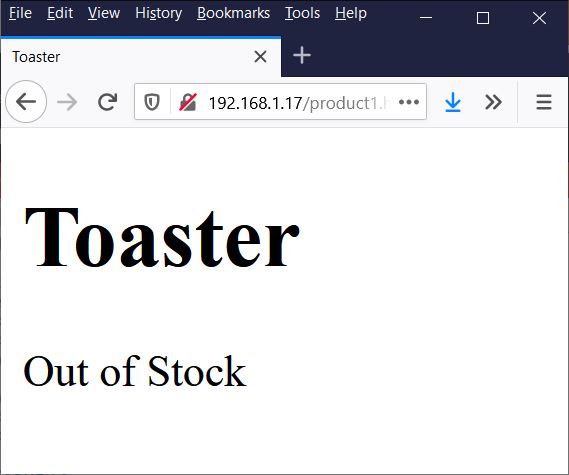

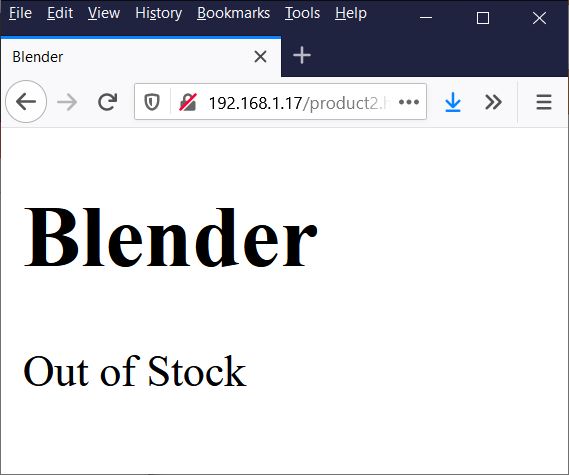

I’ll describe how I did it using a fake website with only two product pages. The product pages are bare-bones, but they get the point across, and the same approach would work on a real website. I’ll create two pages, one for a toaster and one for a blender, to keep the example simple. Here is the HTML for the toaster webpage.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Toaster</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1 class = "title">Toaster</h1>

<span class = "availability">

<span>In Stock</span>

</span>

</body>

</html>

This part isn’t necessary, but to make the demonstration more true-to-life I fired up a virtual machine and installed NGINX. Then I put my two product pages in the root of the server. Here’s what they look like.

Example page for Toaster

And for Blender

Python

So I’ve never actually had a course on the Python programming language, and I’ve never actually sat down and tried to learn it properly. I have used it a ton at work for things like writing test applications that do things like send a bunch of HTTP requests to an embedded system to get data from a control board, so I have had some experience doing this kind of thing. There are probably better ways to do what I did here, but this works.

I created a class called Product with attributes for the url, name of the product, and the product’s availability. I’ve also given the Product class an attribute called statusChanged that will change from False to True when the availability of a product changes. The class also has two member functions, a private member function __getAvailability() and a public member function update(). Here’s a UML diagram of this class.

UML Diagram of Product class.

The private member function __getAvailability() is called at instantiation and by the update function. First, it uses the requests library to send a get request to the Product’s URL. Then it uses the lxml library to turn the HTML response into a tree. It then traverses the tree looking for elements with the class ‘title’ and ‘availability’, updating Product’s title and availability attributes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

def __getAvailability(self):

try:

page = requests.get(self.url)

except:

print('Could not get webpage.')

return

tree = html.document_fromstring(page.text)

productAvailability = []

for element in tree.iter():

if self.name == '':

if element.get('class') == 'title':

self.name = element.text_content()

if element.get('class') == 'availability':

for child in element:

if child.text_content() != '':

productAvailability.append(child.text_content())

self.availability = "".join(productAvailability)

The public member function update() calls the __getAvailability() function, and if the element with the class ‘availability’ has a different value than Product’s availability attribute, it sets Product’s statusChanged flag to True.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

def update(self):

previousAvailibity = self.availability

self.__getAvailability()

if self.availability != previousAvailibity:

self.statusChanged = True

else:

self.statusChanged = False

return self.statusChanged

The main function reads in URL’s that we would like to watch for status changes from a file, and then creates a list of products. It then enters an infinite loop, where it loops through the list of products and updates each one. If the product’s statusChanged flag is True, the main function calls the notify function (well get to that in a second) and passes in the product’s name and availability.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

def main():

# Create list of items

products = []

with open('url_list.txt') as file:

for line in file:

products.append(product(line.rstrip()))

sleep(1)

while True:

for item in products:

sleep(60*30)

if item.update():

notify(item.name, item.availability)

Notification

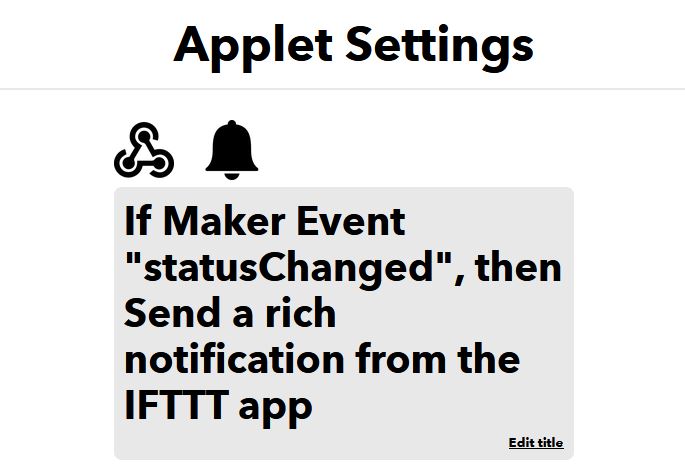

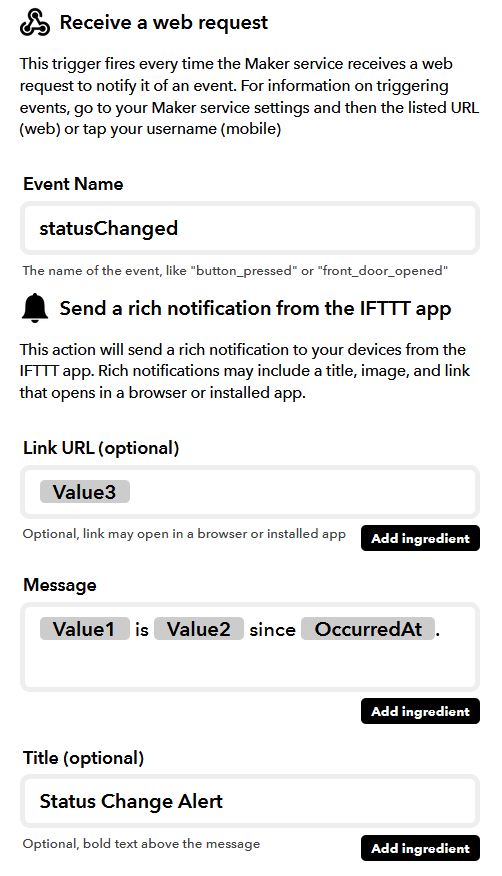

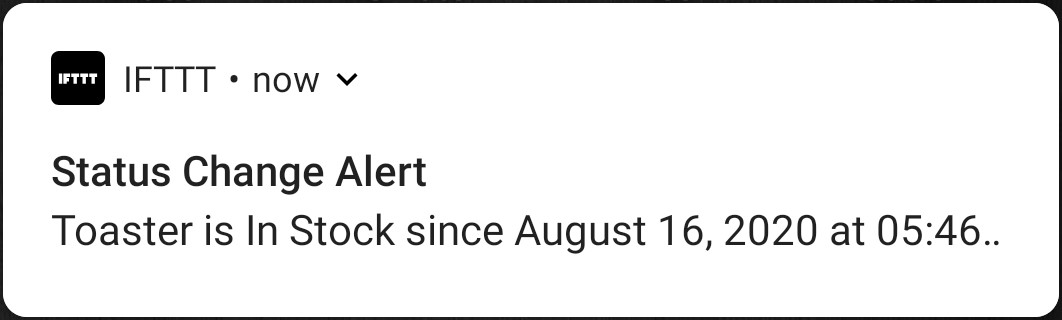

I wanted my python script to be able to send a notification to my phone when the status of a product changed. I didn’t want to dive into complicated server-side programming, so I turned to an extremely useful and free service, IFTTT. I had heard of home-automation geeks using IFTTT to bridge the gaps between different pieces of smart-home tech, but I had never actually tried it myself. It turns out IFTTT has a service exactly for reacting to web requests called Webhooks. IFTTT can also send notifications to your phone if you have the app installed on your phone. I created an IFFT applied with the following settings:

The notify function sends a post request to the IFTTT applet. The post request must contain the unique user IFTTT key, which I won’t show here for obvious reasons.

1

2

3

4

5

def notify(name, availability):

try:

requests.post('https://maker.ifttt.com/trigger/statusChanged/with/key/{}'.format(ifttt_key), json = { 'value1' : name, 'value2' : availability })

except:

print("Request failed.")

Testing It Out

To try it all out I set the sleep time to 10 seconds. If you are going to use this on a real website, make the sleep time a lot longer. I started the python script, waited a few seconds, and edited one of the product pages on the webserver on my virtual machine. In about a minute I got the notification on my phone. It worked!

You can see the whole source code on my Github here.